Zeus sits on his throne. He rules the sky and the world. His sister-wife Hera rules him. Duties and domains in the mortal sphere are parcelled out to his family, the other ten Olympian gods. In the early days of gods and men, the divine trod the earth with mortals, befriended them, ravished them, coupled with them, punished them, tormented them, transformed them into flowers, trees, birds and bugs and in all ways interacted, intersected, intertwined, interbred, and interfered with us. But over time, as age has succeeded age and humankind has grown and prospered, the intensity of these interrelations has slowly diminished. In the age we enter now, the gods are still very much around, favouring, disfavouring, directing and disturbing. Prometheus´s gift of fire has given humankind the ability to run its own affairs, build up its distinct city states, kingdoms and dynasties. The fire is real and hot in the world and has given mankind the power to smelt, forge, fabricate and make, but it is the inner fire too; thanks to Prometheus we are now endowed with the divine spark, the creative fire, the consciousness that once belonged only to the gods.

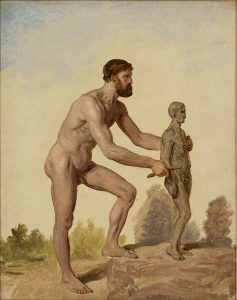

The Golden age of the gods has become an Age of Heroes – men and women who grasp their destinies, use their human qualities of courage, cunning, ambition, speed and strength to perform astonishing deeds, vanquish terrible monsters and establish great cultures and lineages that change the world. The divine fire stolen from heaven by their champion Prometheus burns within them. They fear, respect and worship their paternal gods, but somewhere inside they know they are a match for them. Humanity has entered its teenage years. Prometheus himself – the titan who made us, befriended us and championed us – continues to endure his terrible punishment: shackled to the side of a mountain he is visited each day by a bird of prey that soars down out of the sun to tear open his side, pull out his liver and eat it before his very eyes. Since he is immortal the liver regenerates overnight, only for the torment to repeat the next day

Mankind meanwhile gets on with the mortal business of striving, toiling, living, loving and dying in a world still populated with more or less benevolent nymphs, fauns, satyrs and other spirits of the seas, rivers, mountains, meadows, forests and fields, but bristling too with its share of serpents and dragons – many of them the descendants of the primordial Gaia, the earth goddess and tartarus, god of the depths beneath the earth. Their offspring, the monstrous echidna and typhoon, have spawned a multitude of venomous and mutant creatures, earthborn monsters that ravage the countryside and oceans that humans are trying to tame and endangering mankind by threatening to choke the rise of civilization. So long as Dragons, giants, centaurs and mutant beasts infested the air, earth and seas we could never spread out with confidence and transform the wild world into a place of safety for humans. To survive in such a world, mortals felt the need to supplicate and submit themselves to the gods, to sacrifice to them and flatter them with praise and prayer. But some men and women are beginning to rely on their own resources of fortitude and wit. These are the men and women who – either with or without the help of the gods – will dare to make the world safe for humans to flourish. These are the heroes.

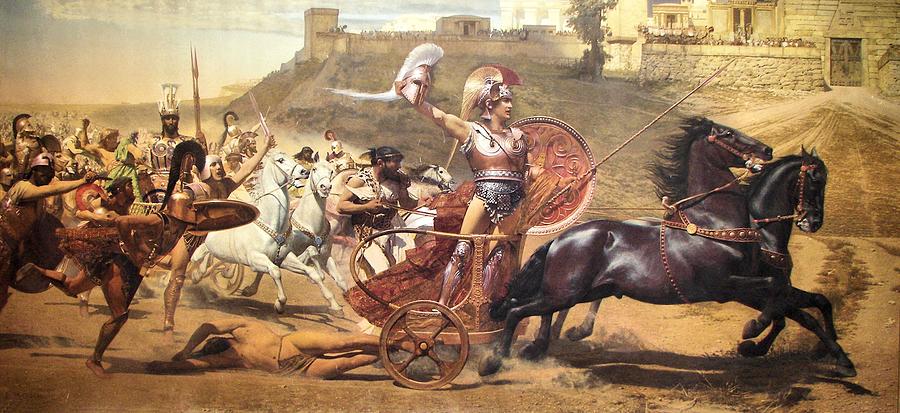

It is important to note that there is a difference between the classical hero, and the modern or medieval ones. A classical hero is considered to be a “warrior who lives and dies in the pursuit of honor” and asserts their greatness by “the brilliancy and efficiency with which they kill”. Each classical hero’s life focuses on fighting, which occurs in war or during an epic quest. Classical heroes are commonly semi-divine and extraordinarily gifted, like Archilles, Heracles or Theseus evolving into heroic characters through their perilous circumstances. While these heroes are incredibly resourceful and skilled, they are often foolhardy, court disaster, risk their followers’ lives for trivial matters, and behave arrogantly in a childlike manner. Medieval and modern heroes generally performed their deeds for the common good instead of the classical goal of individual pride and fame.

Many Greek heroes were mongrel offspring of humans, minor deities, demigods and even full Olympians. Some were born to prophetic curses that caused them to be outcast and raised by foster parent or even foster animals. A great many others would find their divine lineage a curse. Their heroism perhaps derived from their ability to bring their mix of the human and the divine to bear against the grinding pressure of fate. Heroes in myth often had close but conflicted relationships with the gods. Fate, or destiny, also plays a massive role in the stories of classical heroes. The gods in Greek Mythology, when interacting with the heroes, often foreshadow the hero’s eventual death on the battlefield. Countless heroes and gods go to great lengths to alter their pre-destined fate, but with no success, as no immortal can change their prescribed outcomes by the three Fates.

Oedipus and Antigone exile from Thebes, Eugene-Ernest Hillemacher, 1843.

The most prominent example of this is found in the text Oedipus Rex. After learning that his son, Oedipus, will end up killing him, the King of Thebes, Laius, takes huge steps to assure his son’s death by removing him from the kingdom. But, Oedipus slays his father without an afterthought when he unknowingly encounters him in a dispute on the road many years later. The lack of recognition enabled Oedipus to slay his father, ironically further binding his father to his fate.

One of the most well known classical hero´s with a tragic story is Heracles. Heracles was an extremely passionate and emotional individual, capable of doing both great deeds for his friends and being a terrible enemy who would wreak horrible vengeance on those who crossed him. His story is interesting not only because of his strengths and all the heroic things he did during his lifetime, but also because of the flaws that were part of his personality. He is a great example of how a hero whose purpose it was to rid the world of monsters can be in some way become a monster himself . This is Heracles’ story.

Heracles: Son of Zeus and Alcmede (a grandchild of Perseus)

A dream prophecy from Hera foretold that a hero would be born from the line of Perseus which would help and save the Olympians during their war with the giants.

Zeus who was well known for not being loyal to his wife decided after hearing about this prophecy to check up on the line of Perseus. While doing so he discovered that the granddaughter of Perseus was quite beautiful. Zeus was the father of Perseus so this made him the great grandfather of the girl he was about to impregnate.

Hera discovered Zeus´ betrayal and instead of punishing Zeus she directed her anger towards Heracles and she would torment and punish Heracles for most of his life. This started not long after Heracles was born.

As a baby he strangled two deadly snakes that were send by the jealous Hera to kill him.

When growing up he received the kind of education usual for children of a royal house in those days. Chariot driving, javelin and discus throwing, track running, archery, horse riding as well as, rhetoric, mathematics, and music, It was noticed by his teachers that despite the boys amiable and friendly nature, he also possessed a fiery and furious temper. This came to light when one of his teachers after losing his patience struck Heracles and payed for it with his life. The rest of his schooling revealed that while nature and fate may have gifted Heracles with many fine attributes, wit and wisdom, craft and cunning were not foremost among them. The reputation of Heracles began to grow when he slew a fierce lion on Mount Cithaeron when he was eighteen years old. Not soon after he single handedly defended Thebes against an attack from King Erginos of Orchomenos. As thanks the king of Thebes offered Heracles the hand of his daughter Megara.

Heracles’ life in Thebes was almost modern in its rhythms. Each day he would kiss goodbye to his wife Megara and children and go off to work, killing monsters and toppling tyrants. Life was good. One fateful evening Heracles returned to his home and was met by two small but fierce and burning eyed demons in the doorway. He charged them at once, grappling them to the floor and crushing their backs, suddenly a great dragon came screaming out of the house towards him, he rushed at it, closed his hands around its scaly neck and squeezed with all his strength. Only when the life went out of the monster and it slipped dead to floor did Hera lift the mist of delusion she had visited upon him. Looking down, he now saw with appalling clarity that the dragon he had killed was his wife Megara and the two demons were his beloved children.

It was one of Hera’s cruellest interventions, and evidence of the unfathomable depth of her hatred. To take in one swift and irreversible moment everything that mattered to him. Not just those he loved most, but his reputation too. When news broke of what he had done, no one would speak to, or come near to him. He was polluted. Heracles’grief was overpowering. He wanted to die. But knew that he must punish himself by undergoing an unrelenting penance. Only then would he feel fit to meet the souls of Megara and his children in the underworld. Without purification from a king, oracle, priest or priestess, those responsible for blood crimes had to attempt to cleanse themselves by a life of exile and atonement. If they failed to expiate their crimes, the wild furies would rise up from Erebus and chase them down, flailing them with iron wips until they went mad.

Heracles exiled himself from Thebes, and went on his knees to Delphi to seek guidance

‘to atone for his abominable crimes, Heracles must take himself to Tiryns and supplicate himself before the throne,’ Heracles could not know this but the priestess had been entranced by Hera and the words were hers. ‘For ten years he must serve without question,’ the priestess continued ‘whatever he is told to do, Heracles must do. Whatever tasks he is set to perform, these Heracles must willingly undertake. Only then he can be free’. This is how his twelve labours started.

These labours include the killing of fearsome creatures (the Nemean Lion, the Lernaean Hydra), the capture of mystical creatures, ( The Ceryneian hind, the Erymanthian boar, the Cretan bull, the mares of Diomedes, the cattle of Geryon and Cerberus) The cleaning of the Augean stables, getting rid of the Stymphalian birds, capturing the girdle of Hippolyta the queen of the amazons and retrieving the golden apples of Hesperides.

During his quest to retrieve the golden apples of Hesperides Heracles came upon an old friend of ours.

‘welcome, Heracles. I have been expecting you.’ Heracles looked up and shaded his eyes against the sun. A figure was chained to the rock. ‘Prometheus?’

Who else could it be? Zeus had shackled the Titan to the side of a vast mountain and daily send an eagle to tear out and devour the titans liver. Each night, Prometheus being immortal the liver grew back and the following day the torture began anew. Countless generations of the race of men and women had risen, fallen and risen since their creator and champion had been made to endure these agonies. Heracles knew who this figure chained to the rocks was, everybody did. But only Heracles dared to raise his bow and shoot down Zeus’ avenging eagle as it soared out of the sun towards them. It did not take Heracles long to shatter Prometheus’s manacles with a blow of his club.

‘thank you Heracles,’ said the titan rubbing his shins. ‘You have no idea how much i have been looking forward to this moment.’

After his liberation Prometheus gave Heracles the advice he needed to find the golden apples of Hesperides by pointing him in the direction of his brother Atlas who as a punishment was carrying the weight of the heavens on his shoulders. After Heracles and Prometheus parted ways, Prometheus went to Zeus, who forgave him and embraced him as a friend again. Both Heracles and Prometheus had a final part to play in the dream prophecy made by Hera. They would save the Olympian gods from the giants. For all his achievements Zeus made Heracles immortal after his death.

Heracles was the strongest man who ever lived. No human and almost no immortal creature, ever subdued him physically. With uncomplaining patience he bore the trials and catastrophes that were heaped upon him in his turbulent lifetime. With his strength came, as we have seen, a clumsiness which, allied to his apocalyptic bursts of temper, could cause death or injury to anyone who got in the way. Where others were cunning and clever, he was direct and simple. Where they planned ahead, he blundered in, swinging his club, roaring like a bull. Mostly these shortcomings were more endearing than alienating. He was not, as the duping of atlas and the manipulation of Hades showed, entirely without that quality of sense, gumption and practical imagination that the Greeks call nous. He possessed saving graces that more than made up for his exasperating faults. His sympathy for others and willingness to help those in distress was bottomless, as were his sorrow and shame that overcame him when he made mistakes and people got hurt. He proved himself prepared to sacrifice his own happiness for years at a stretch in order to make amends for the usually unintentional harm he caused. His childishness, therefore, was offset by a child like lack of guile or pretence as well as a quality that is often overlooked when we catalogue the virtues: fortitude- the capacity to endure without complaint. For all his life he was persecuted, plagued and tormented by a cruel, malicious and remorseless deity pursuing a vendetta which punished him for a crime for which he could be in no way held responsible – his birth. No labour was more Heraclean than the labour of being Heracles. In his uncomplaining life of pain and persistence, in his compassion and desire to do the right thing, he showed greatness of soul. Heracles may not have possessed the pert agility and charm of Perseus and Bellerophon, or the intellect of Oedipus, the talent for leadership of Jason or the wit and imagination of Theseus, but he had a feeling heart that was stronger and warmer than any of theirs.

Many of the teksts in this post are from the book Heroes written by Stephen Fry, all credits go to him.

For more about Greek mythology I recommend the following:

Theogony by Hesiod, translated by M.L. West.

The Library of Greek Mythology by Apollodorus, translated by Robin Hard.

Myth and Philosophy: A Contest of Truths by Lawrence J. Hatab.

The Iliad and Odyssey by Homer, translated by Robert Fagles.

Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes by Edith Hamilton.

Mythos and Heroes by Stephen Fry.