I first read about the Spartans when I was about 15 years old. During this phase of my life, like a lot of other children, I started to figure out who I was and who I wanted to be. I was looking for role models and the Spartans made a lasting impression on me. The first book I read about Spartan society and culture was Gates of fire, a fictional history book about the battle of Thermopylae fought in the year 480 BC between the Greek allies and the Persian empire which is written by Steven Pressfield. I have been studying their culture ever since. Unfortunately there are limited sources about Spartan culture and society. The Spartans didn’t leave much behind in the sense of writing, art, music or architecture. Most of the sources we do have are not Spartan, but outsiders writing about the Spartans, so it is difficult to figure out if those sources are objectively written. Some of the more well known ancient sources are: Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, Aristotle and Plutarch. So take in consideration that in this text I will be relying heavily on their works but also on the works of Steven Pressfield whom I consider to be one of the greatest living specialists on this subject.

Sparta was unique in ancient Greece for its social system and constitution, which configured its entire society to maximize military proficiency at all costs, focusing all social institutions on military training and physical development. Its inhabitants were classified as Spartiates (Spartan citizens with full rights), mothakes (non-Spartan free men raised as Spartans), perioikoi (free residents who worked as craftsmen and traders, and built weapons for the Spartans), and helots (state-owned serfs, enslaved non-Spartan local population).

Lycurgus

All warrior cultures start with a great man. In ancient Sparta that man was Lycurgus. Between the 8th and 7th centuries BC the Spartans experienced a period of lawlessness and civil strife, later attested by both Herodotus and Thucydides. As a result, they carried out a series of political and social reforms in their own society, these reforms were attributed to Lycurgus. There is no real confirmation that the man truly existed, so some of his deeds can be placed in the mists of myth. His reforms mark the beginning of the history of Classical Sparta.

Lycurgus took the city from a normal society to a warrior culture. And so that no man would have grounds to feel superior to another, Lycurgus divided the country into 9000 equal plots of land. To each family, he gave one plot. Further, he decreed that the men no longer be called citizens but peer or equals. So that no man might compete with another or consider themselves better. Lycurgus outlawed money. A coin sufficient to purchase a loaf of bread was made of iron, the size of a man´s head and weighting about 14 kilo. So ridiculous was such a coinage that men no longer coveted wealth but pursued virtue instead. Lycurgus outlawed all occupations except warrior. He decreed that no name could be inscribed on a tombstone except that of a woman who died in childbirth or a man killed on the battlefield. A Spartan entered the army at eighteen and remained in service till he was sixty; he regarded all other occupations as unfitting for man.

Lycurgus decreed that no man under thirty could eat dinner at home with his family. Instead, he instituted ´common messes´ of fourteen or fifteen men. The point of the common mess was to bind the men together as friends. The payoff came , of course on the battlefield.

Here is how Spartans got married. Lycurgus wanted to encourage passion, because he felt that a child- a boy- conceived in the heat of passion would make a better warrior. So a young Spartan husband could not live with his bride (he spend all day training and slept in the common mess). If the couple were to consummate their love, the husband had to sneak away from his messmates, then slip back before his absence was discovered. It was not uncommon for a young husband to be married for four or five years and never see his bride in daylight, except during public events and religious festivals.

Since no Spartiate was allowed to have another occupation than warrior, practically everything else was done by the helots, the enslaved Greeks, who handled all the day-to-day tasks and unskilled labour required to keep society functioning: They were farmers, domestic servants, nurses and military attendants. Without this huge population of slaves it would not be possible for the Spartans to focus on their education and life as warriors and because Spartan citizenship was inherited by blood, Sparta always faced a helot population that vastly outnumbered its citizens. As you might imagine the Spartans were quite nervous about revolt, and one of the ways they dealt with this problem was by declaring war on their helot population each year, so as to be able to kill helots without having to deal with ritual pollution. Some sources tell about the existence of an organisation called the krypteia, for which the strongest, and best of the young Spartans were selected. They supposedly hunted down and killed the most likely helots to cause problems. Despite those efforts the revolts did happen, some of which nearly destroyed Sparta.

The Agoge

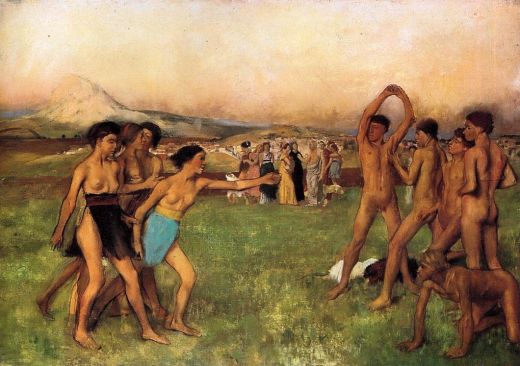

Growing up as a Spartan was brutal. Sources say that every new born boy was brought before the gerousia to be examined for physical hardiness. If a child was judged unfit, he was taken to a wild gorge on Mount Taygetos, the mountain overlooking the city, and left for the wolves. Archaeologists have not found any remains of babies in the described area, so we cannot be sure that this practise was real. Although the study of other cities and cultures in this period suggests that this practise happened in a lot of places. In Sparta, boys were allowed to stay with their mothers till they were seven. At that age, they were taken from their families and enrolled in the agoge ´the upbringing´. This training lasted till they were eighteen, when they were considered grown warriors and were enrolled in the army. The boys in training were given one garment, a rough cloak that was worn all year long. They slept outdoors year- round. Each boy carried a sickle- like weapon called a xyele. They were allowed no beds but instead had to make nests of reeds gathered each night from the river. They were not permitted to cut the reeds with their sickles but had to tear them with their bare hands. Food for the boys was pig´s blood porridge. Bad as the food was, the boys got little of it. Instead, they were encouraged to steal. Stealing was no crime but getting caught was. A boy who was caught got whipped. To cry out was considered a sign of cowardice. It was not unheard of for a Spartan boy to die of a beating without uttering a word.[1]

The agoge, trained the mind as well as the body. Spartans were not only literate, but admired for their intellectual culture and poetry. Socrates said the “most ancient and fertile homes of philosophy among the Greeks are Crete and Sparta, where are found more sophists than anywhere on earth.”[2] Public education was provided for girls as well as boys, and consequently literacy rate was higher in Sparta than in other Greek city-states. Self-discipline and physical toughness was the goal of Spartan education. Sparta placed the values of liberty, equality, and fraternity at the centre of their ethical system.

Dual Kingship

Sparta was an oligarchy[3]. The state was ruled by two hereditary kings of the Agiad and Eurypontid families, both supposedly descendants of our old friend Heracles and equal in authority, so that one could not act against the power and political enactments of his colleague. The duties of the kings were primarily religious, judicial, and military. As chief priests of the state, they maintained communication with the Oracle of Delphi, whose pronouncements strongly influenced Spartan politics. Civil and criminal cases were decided by a group of officials known as the ephors, as well as a council of elders known as the gerousia. The gerousia consisted of 28 elders over the age of 60, elected for life and usually part of the royal households, and the two kings. High state decisions were discussed by this council, who could then propose policies to the damos, the collective body of Spartan citizenry, who would select one of the alternatives by vote.[4]

The battle of Thermopylae

One of the most famous Spartans is King Leonidas who in 480BC led a small force and made a legendary last stand at the battle of Thermopylae against a massive Persian army, inflicting very high casualties on the Persian forces before finally being overwhelmed. Most people know about this last stand through the movie 300 (2007). Which unfortunately is full of lies. Never take anything made in Hollywood as accurate history. I will do you the courtesy to tell you what we do know about this last stand because it gives us a valuable insight in how the Spartans operated.

To understand the significance of this moment we have to move back a bit in time to see where the conflict between the Persian empire and the Greeks started. In 490 BC the battle of Marathon took place in which the Athenians defeated a Persian invasion force. Athens provoked this attack when they aided the Ionian cities (In modern day Turkey) in becoming independent from their ruler Darius of the Persian empire. Darius swore to burn down Athens as payback but failed after his invading army was defeated at the battle of Marathon. This defeat only made Darius more determined, so he started building up a huge army to invade and conquer all of Greece but before this army was completed he died. His son Xerxes decided to uphold his fathers promise and by 480 BC he had amassed a huge army and navy, and set out to conquer all of Greece. It was said this army was so big it drank the rivers dry.

The Spartans had consulted the Oracle at Delphi earlier in the year. The Oracle is said to have made the following prophecy:

O ye men who dwell in the streets of broad Lacedaemon!

Honour the festival of the Carneia!! Otherwise,

Either your glorious town shall be sacked by the children of Perseus,

Or, in exchange, must all through the whole Laconian country

Mourn for the loss of a king, descendant of great Heracles.

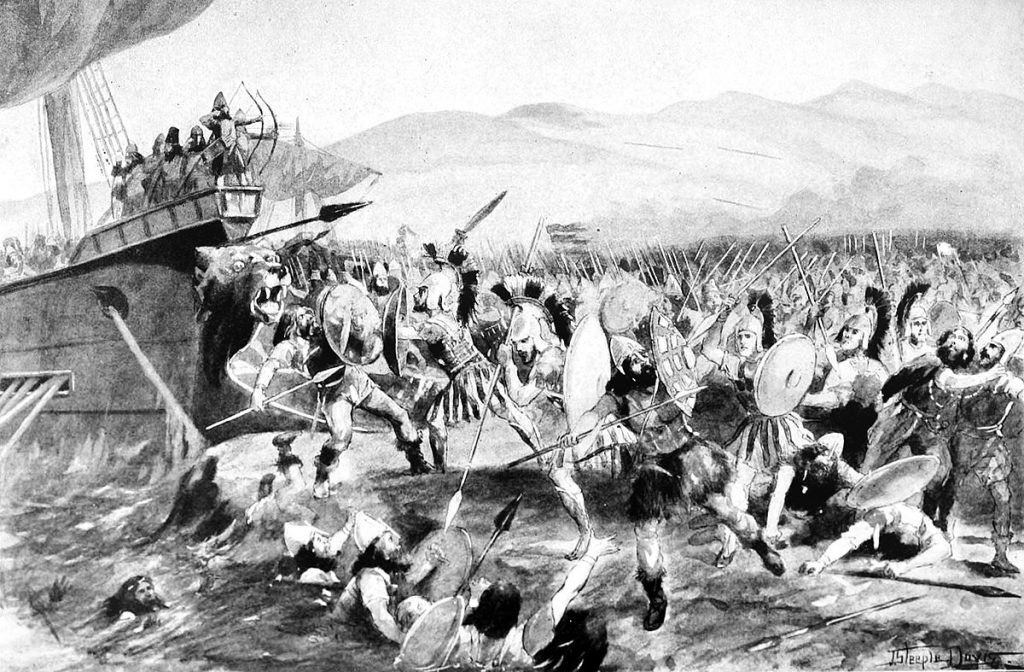

Herodotus tells us that Leonidas, in line with the prophecy, was convinced he was going to certain death since his forces were not adequate for a victory, and so he selected only Spartans with living sons. The Spartan force was reinforced on route to Thermopylae by contingents from various cities and numbered more than 7,000 by the time it arrived at the pass. Leonidas chose to camp at, and defend, the “middle gate”, the narrowest part of the pass of Thermopylae, where the Phocians had built a defensive wall some time before. News also reached Leonidas, from the nearby city of Trachis, that there was a mountain track that could be used to outflank the pass of Thermopylae. Leonidas stationed 1,000 Phocians on the heights to prevent such a manoeuvre. Xerxes sent a Persian emissary to negotiate with Leonidas. The Greeks were offered their freedom, the title “Friends of the Persian People”, and the opportunity to re-settle on land better than that they possessed. When Leonidas refused these terms, the ambassador carried a written message by Xerxes, asking him to “Hand over your arms”. Leonidas’ famous response to the Persians was “Molṑn labé“ usually translated as “come and take them”. With the Persian embassy returning empty-handed, battle became inevitable. Spartans were known for their short and powerful remarks or replies. Another famous one that was made during the battle of Thermopylae was: When one of the soldiers said that, ” when the Barbarians discharged their arrows they obscured the light of the sun by the multitude of the arrows, so great is the number of their host”, A Spartan called Deniekes replied, “Good, then we shall have our battle in the shade”.

Xerxes delayed for four days, giving the Greeks a chance to disperse, before sending troops to attack them. After 2 days of fighting and huge losses for the Persian army (most notably his elite royal guard regiment the immortals who were badly mauled by the Greeks) a local resident named Ephialtes betrayed the Greeks by revealing this mountain track that led behind the Greek lines. Leonidas, aware that his force was being outflanked, dismissed the bulk of the Greek army and remained to guard their retreat with 300 Spartans and 700 Thespians, fighting to the death. Others also reportedly remained, including up to 900 helots and 400 Thebans.

At dawn, Xerxes made libations, pausing to allow the Immortals sufficient time to descend the mountain, and then began his advance. A Persian force of 10,000 men, comprising light infantry and cavalry, charged at the front of the Greek formation. The Greeks this time came forth from the wall to meet the Persians in the wider part of the pass, in an attempt to slaughter as many Persians as they could. They fought with spears, until every spear was shattered, and then switched to xiphē (short swords).In this struggle, Herodotus states that two of Xerxes’ brothers fell: Abrocomes and Hyperanthes. Leonidas also died in the assault, shot down by Persian archers, and the two sides fought over his body; the Greeks took possession. As the Immortals approached, the Greeks withdrew and took a stand on a hill behind the wall. Of the remaining defenders, Herodotus says: Every one of the 300 Spartans died resisting the Persian invaders except one, a warrior named Aristodemus who was withdrawn at the last minute rendering him temporary blind. The next year, the Spartans again faced the Persians at Plataea, in central Greece. This time, Aristodemus was healthy and fought in the front rank. When the battle was over, all who witnessed his actions agreed that Aristodemus had earned the prize of valour, so brilliant and relentless had been his courage. But the gerousia refused to award him this honour, judging that he was driven by such shame that he risked his life recklessly, deliberately seeking to die.[5]

To explain this let me tell you more about the laconic code of honour which applied to all Spartans. No soldier was considered superior to another. Suicidal recklessness and rage were prohibited in the Spartan army, as these behaviours endangered the phalanx[6]. Recklessness could lead to dishonour, as in the case of Aristodemus[7] Spartans regarded those who fight, while still wishing to live, as more valorous than those who don’t care if they die. They believed that a warrior must not fight with raging anger, but with calmed determination. Losing a sword and a spear was tolerated. But to lose a shield was a sign of disgrace. Since the shields overlapped while in the fighting formation, it not only served to protect the person holding it, but the person to his left as well and by extend the whole phalanx. To come home without the shield was the mark of a deserter.

Leonidas’ actions have been the subject of much discussion. It is commonly stated that the Spartans were obeying the laws of Sparta by not retreating. It has also been proposed that it was the failure to retreat from Thermopylae that gave rise to the notion that Spartans never retreated. It has also been suggested that Leonidas, recalling the words of the Oracle, was committed to sacrificing his life in order to save Sparta. Spartans were taught it was their duty to die for their country. Their life was lived in service of their community. It was unusual for Spartans to commemorate except through a minimalistic gravestone, but for the warriors that died at Thermopylae the poet Simonides of Ceos wrote an epitaph which can still be found at the site of the battle:

Go tell the Spartans, passerby:

That here, by Spartan law, we lie

It was well known in ancient Greece that all the Spartans who had been sent to Thermopylae had been killed there, and the epitaph works with the idea that there was nobody left to bring the news of their deeds back to Sparta. Greek epitaphs often appealed to the passing reader for sympathy, but the epitaph for the dead Spartans at Thermopylae took this convention much further than usual, asking the reader to make a personal journey to Sparta to break the news that the Spartan expeditionary force had been wiped out. The stranger is also asked to stress that the Spartans died ‘fulfilling their orders’.

Sparta´s decline

At its peak around 500 BC, Sparta had some 20,000–35,000 citizens, plus numerous helots and perioikoi. The likely total of 40,000–50,000 made Sparta one of the larger Greek city-states.[1] After the destruction of the invading force from Persia in 480BC Sparta and Athens were considered the victors but both dealt differently with this victory.

Athens´ ambitions were to create an empire while Sparta just wanted to be left alone, basically continuing the way the had since Lycurgus created their system. Athenian aggression and ambitions provoked the Spartans in self defensive action which lead to the Peloponnesian war which started in 431BC and ended in 404 BC leaving Sparta as victor. Spartan ascendancy did not last long. By the end of the 5th century BC, Sparta had suffered serious casualties in the Peloponnesian Wars, and its conservative and narrow minded mentality alienated many of its former allies. True to their nature they kept fighting the Persians, Athenians, Thebans, and Argives until in 371 BC Sparta suffered a severe military defeat to Epaminondas of Thebes at the Battle of Leuctra. This was the first time that a full strength Spartan army lost a land battle. Nonetheless, it was able to continue as a regional power for over two centuries. Neither Philip II nor his son Alexander the Great attempted to conquer Sparta itself. Even during its decline, Sparta never forgot its claim to be the “defender of Hellenism” and its Laconic wit. An anecdote has it that when Philip II sent a message to Sparta saying “If I enter Laconia, I will raze Sparta”, the Spartans responded with the single, reply: αἴκα, “if”

So after all you have read you might find it strange that I have so much respect for the Spartans and their culture. They captured and held a large population of slaves which they treated badly: let’s not forget the killing that took place. But to put it more into a time period, slavery was quite normal in the Greek and Persian world. The Spartan slaves though at risk of being killed, were granted more freedom and rights than the slaves in most other cities in Greece. Families stayed together, they were allowed to keep 50% of their produce and had the possibility to accumulate wealth and buy their freedom. But to make it clear, slavery was and is horrible.

Another thing that I imagine a lot of people find difficult to digest is the agoge. Pitting children against each other, beatings and exercises that could lead to death. But also the simple fact that these children had no chance to be children. From their birth till their death they were owned by their society. You are right that this is a crime, but we should remember that the world they lived in was brutal, losing a war might mean your city and all its people would be enslaved or killed. Considering that fact the Spartans did quite well in keeping their lands safe for such a long period of time.

One of the things I started looking for from a young age was friendship, people who will put themselves on the line for me while I do the same for them. Which was difficult to find in our individualistic society. The Spartans had a way to achieve this strong bond, by sharing hardships and joy while growing up together. The agoge, although very brutal, partly helped in creating this strong bonding. It promoted selflessness, love and loyalty to one´s comrades in an individual, which I find beautiful qualities to have.

The Spartans are still known for their avoidance of luxury and comfort. They outlawed money from their society so that people would not coveted wealth and so that it would not be a distraction in their pursuit of virtue. Living in a capitalistic society we all know that money can corrupt, distract, and destroy. It is such a major part in our lives that it sometimes blinds us from more important things. Try to imagine how you would spend your time if you would not have to concern yourself with money, but instead were pushed towards virtue. I think the world would be a better place.

Another thing the Spartans have taught me is that there is satisfaction in pushing yourself to your limit and extending it, to do it you need discipline, endurance and patience. It is scary to push yourself to your limit to see what you are capable of because the result might be disappointing, maybe that’s why so few of us ever try to really get the best out of ourselves.

[1] Pressfield, S. (2011). The Warrior Ethos. New York: Black Irish Entertainment LLC.

[2] Alexander the Great and his time. By Agnes Savill. p. 44

[3] A small group of the elite ruled the country.

[4] the Politics By Aristotle, Thomas Alan Sinclair, Trevor J. Saunders

[5] Pressfield, S. (2011). The Warrior Ethos. New York: Black Irish Entertainment LLC. p. 23.

[6] a block of heavily armed infantry standing shoulder to shoulder in files several ranks deep.

[7] Michell, Humfrey (1964). Sparta. Cambridge University Press. p. 175.